Disclaimer: This post is based upon experiences I found when sending malware via GMail (Google Mail). I'm documenting them here for others to: disprove, debate, confirm, or to downplay its importance.

Update:

In the comments below, a member of Google's AntiVirus Infrastructure team provided insight into this issue. A third-party AV engine used by GMail was designed by the third-party to automatically open ZIP files with a password of 'infected'. I want to thank Google for their attention to the matter as it shows that there was no ill-intent or deliberate scanning.

As a professional malware analyst and a security researcher, a sizable portion of my work is spent collaborating with other researchers over attack trends and tactics. If I hit a hurdle in my analysis, it's common to just send the binary sample to another researcher with an offset location and say "What does this mean to you?"

That was the case on Valentine's Day, 14 Feb 2014. While working on a malware static analysis blog post, to accompany my

dynamic analysis blog post on the same sample, I reached out to a colleague to see if he had any advice on an easy way to write an IDAPython script (for IDA Pro) to decrypt a set of encrypted strings.

There is a simple, yet standard, practice for doing this type of exchange. Compress the malware sample within a ZIP file and give it a password of '

infected'. We know we're sending malware samples, but need to do it in a way that:

a. an ordinary person cannot obtain the file and accidentally run it;

b. an automated antivirus system cannot detect the malware and prevent it from being sent.

However, on that fateful day, the process stopped. Upon compressing a malware sample, password protecting it, and attaching it to an email I was stopped. GMail registered a Virus Alert on the attachment.

Stunned, I try again to see the same results. My first thought was that I forgot to password-protect the file. I erased the ZIP, recreated it, and received the same results. I tried with a different password - same results. I used a 24-character password... still flagged as malicious.

The instant implications of this initial test were staggering; was Google password cracking each and every ZIP file it received, and had the capability to do 24-character passwords?! No, but close.

Google already opens any standard ZIP file that is attached to emails. The ZIP contents are extracted and scanned for malware, which will prevent its attachment. This is why we password protect them. However, Google is now attempting to guess the password to ZIP files, using the password of 'infected'. If it succeeds, it extracts the contents and scans them for malware.

Google is attempting to unzip password-protected archives by guessing at the passwords. To what extent? We don't know. But we can try to find out.

I obtained the

list of the 25 most common passwords and integrated them (with 'infected') into a simple Python script below:

import subprocess

pws = ["123456","password","12345678","qwerty","abc123","123456789","111111","1234567","iloveyou","adobe123","123123","sunshine","1234567890","letmein","photoshop","1234","monkey","shadow","sunshine","12345","password1","princess","azerty","trustno1","000000","infected"]

for pw in pws:

cmdline = "7z a -p%s %s.zip malware.livebin" % (pw, pw)

subprocess.call(cmdline)

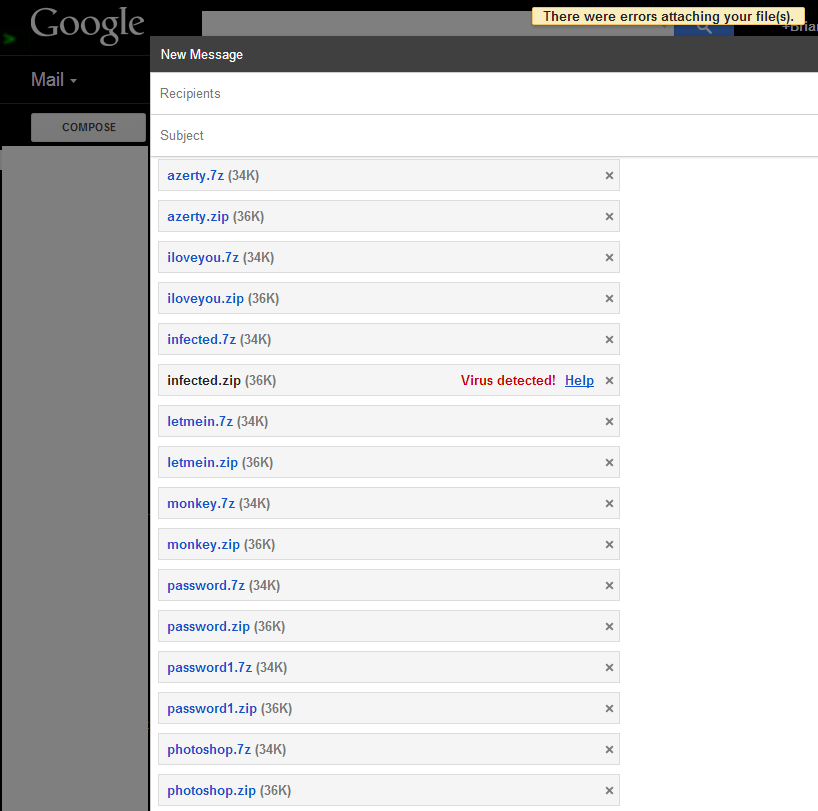

This script simply compressed a known malware sample (malware.livebin) into a ZIP of the same password name. I then repeated these steps to create respective 7zip archives.

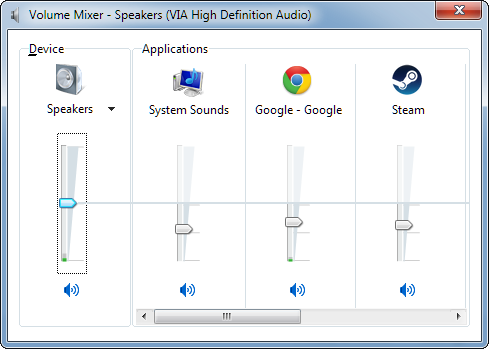

I then created a new email and simply attached all of the files:

Of all the files created, all password protected, and each containing the exact same malware, only the ZIP file with a password of '

infected' was scanned. This suggests that Google likely isn't using a sizable word list, but it's known that they are targeting the password of '

infected'.

To compensate, researchers should now move to a new password scheme, or the use of 7zip archives instead of ZIP.

Further testing was performed to determine why subsequent files were flagged as malicious, even with a complex password. As soon as Google detects a malicious attachment, it will flag that attachment

File Name and prevent your account from attaching any file with the same name for what appears to be five minutes. Therefore, even if I recreated infected.zip with a 50-char password, it would still be flagged. Even if I created infected.zip as an ASCII text document full of spaces, it would still be flagged.

In my layman experience, this is a very scary grey area for active monitoring of malware. In the realm of spear phishing it is common to password protect an email attachment (DOC/PDF/ZIP/EXE) and provide the password in the body to bypass AV scanners. However, I've never seen any attack foolish enough to use a red flag word like "infected", which would scare any common computer user away (... unless someone made a new game called Infected? ... or a malicious leaked album set from Infected Mushroom?)

Regardless of the email contents, if they are sent from one consenting adult to another, in a password-protected container, there is an expectation of privacy between the two that is violated upon attempting to guess passwords en masse.

And why is such activity targeted towards the malware community, who uses this process to help build defenses against such attacks?

Notes:

- Emails were sent from my Google Apps (GAFYD) account.

- Tests were also made using non-descript filenames (e.g. a.txt).

- Additional tests were made to alter the CRC32 hash within the ZIPs (appending random bytes to the end of each file), and any other metadata that could be targeted.

- The password "infected" was not contained in the subject nor body during the process.

Updates:

There was earlier speculation that the samples may have been automatically sent to VirusTotal for scanning. As shown in the comments below, Bernardo Quintero from VirusTotal has denied that this is occurring. I've removed the content from this post to avoid any future confusion.

Others have come forth to say that they've seen this behavior for some time. However, I've been able to happily send around files until late last week. This suggests that the feature is not evenly deployed to all GMail users.

A member of Google's team replied below noting that this activity was due to a third-party antivirus engine used by Google.

The owner of

VirusShare.com, inspired by this exchange, attempted to locate what engine this could be by uploading choice samples to VirusTotal. His uploads showed one commonality, NANO-Antivirus:

My own tests also showed positive hits from NANO-Antivirus.

At the very least, this shows how one minor, well-meaning feature in an obscure antivirus engine can cause waves of doubt and frustration to anyone who decides to use it without thorough testing.